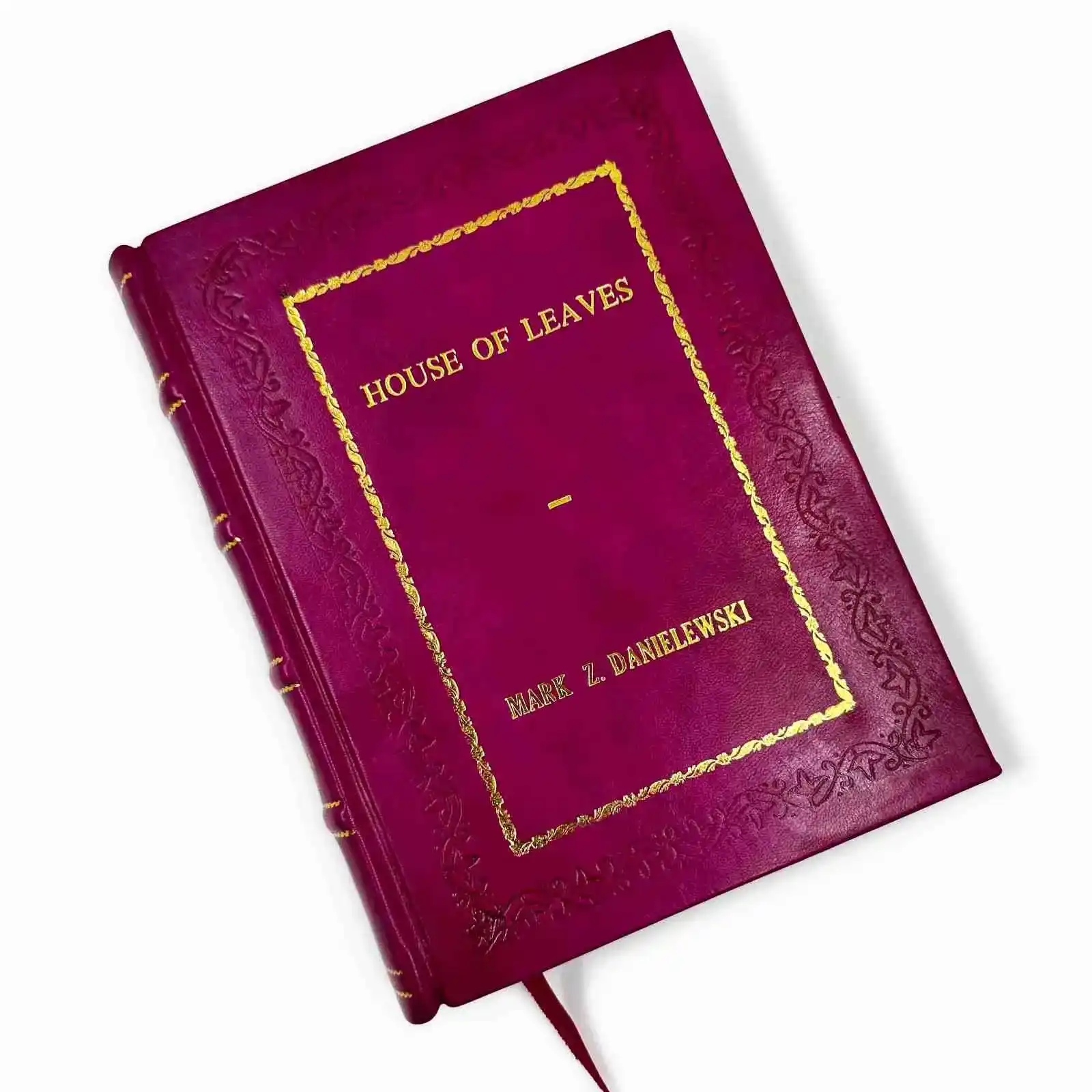

House of Leaves, Mark Z. Danielewski’s metafictional marvel, has long captivated readers with its labyrinthine narrative, typographical daring, and unsettling evocation of the unknown. At its core lies a profound tension between reality and perception, an interplay that not only drives the haunting plot but also implicates the reader in its unsettling power.

1. The Unreliable Narratives: Johnny Truant and Zampanò

The novel presents multiple layers of narration, none of which can be wholly trusted. Zampanò, the first-layer narrator, assembles a scholarly analysis of The Navidson Record, a documentary that may or may not exist. Yet his obsessive commentary, full of contradictory digressions, begs the question: how much of the documentary’s content is reliable, even if it existed?

Johnny Truant, the second-layer narrator, discovers Zampanò’s manuscript after the latter’s death. Johnny’s experiences, erratic behaviors, hallucinations, and psychological unraveling, mirror the destabilizing nature of the house itself. His mental breakdown intersects with Zampanò’s analysis, leaving the reader to sift purple prose, footnotes, and sidebars for shards of truth.

Thus, the narrators’ fractured perspectives form conflicting prisms through which we perceive the story. Reality seems contingent, unstable, subjective, and dangerously malleable.

2. The House as a Mirror: Space, Perception, and the Unknown

The physical manifestation of this theme lies in the house at the center of Navidson’s world: a structure that defies Euclidean geometry. Hallways lengthen and contract, rooms shift, dimensions change without warning. Photographs showing impossible vistas, corridors that reconfigure themselves, these details suggest that the house’s realities are not fixed but mediated by perception.

Navidson, armed with cameras, light meters, and rational caution, attempts to measure and document the house. Yet empirical tools fail him. The house becomes a grotesque Rorschach test, in which subjective fear and the unknowable distort his experience. His rational attempts to master reality are outweighed by the house’s psychological strain. In House of Leaves, perception doesn’t just mediate reality, it constructs it.

3. Typography as Unsettling Mechanism

Danielewski’s typographical innovation becomes a textual reflection of reality’s breakdown. Pages shift orientation, spirals of words descend margins, blank spaces loom where text disappears. Reading becomes an embodied, disorienting act; layout itself mutates the reading experience.

These design choices are not just gimmicks, they mirror the psychological and spatial instability of the story. When you turn the book upside-down to follow a sequence, you’re momentarily inhabiting the disorientation experienced by Navidson within that shifting space. The text itself becomes a manifestation of fractured perception.

4. Documentary vs. Horror: The Blurring of Genre

The novel constantly toggles between documentary analysis and visceral horror. Zampanò’s footnotes mimic academic annotation: citations, references, cross-textual allusions. Yet in the very next moment, Johnny Truant’s voice intrudes with profanity, paranoia, and nightmarish experiences.

Similarly, The Navidson Record is presented as serious documentary footage. Navidson aims to produce a “truthful” record of spatial anomalies. But as the footage becomes corrupted, the documentary’s reliability collapses. Horror bleeds into analysis. We’re left unsure whether we are reading a horror story, a satire, a scholarly treatise or something darker altogether.

Danielewski exploits this ambiguity to challenge the reader: do we trust empirical structures or visceral narrative? Do we privilege measurement or psychological resonance? The novel suggests both are flawed and perception, always, is the final arbiter.

5. The Reader as Participant

Crucially, House of Leaves implicates you, the reader, in this game of perception. Forced to flip pages, confront fractured text, and interpret marginalia, the reader becomes a participant in the chaos. The book refuses passive consumption; you must navigate its instabilities.

This participatory experience mirrors how the characters grapple with their own shifting realities. By physically interacting with the mechanics of the book, you sense how perception can reshape experience. You’re not simply reading about Navidson’s fear, you feel the distortions seep into your own reading.

6. Themes of Loss and Obsession

Beyond the formal structure, House of Leaves embeds powerful emotional subtexts. Navidson’s initial documentation stems from desire: to capture ordinary family life through the lens of art. He returns to his suburban home after combat trauma, hoping to make sense of normalcy. Yet the house defies normalcy, conjuring obsession and fear.

Johnny, too, is haunted by fatherless alienation, by his relationship with the text, by his own failing sanity. His obsession with Zampanò’s manuscript becomes all-consuming, unmooring his sense of self.

In both cases, perception is the battleground of trauma: reality splinters under the weight of grief, guilt, longing. The house externalizes these internal fractures, manifesting subjective fear as objective instability.

7. The Elusive Truth

By novel’s end, the truth remains tantalizingly elusive, if truth can be located at all. The documentary The Navidson Record may be real or invented. Zampanò’s footnotes may be deliberate falsifications. Johnny’s breakdown may be text-generated, or wholly real. The “truth” shifts with microphone static, between film reels, across page breaks.

Perhaps that is Danielewski’s intention: to demonstrate that truth is not a monolith but a refracted spectrum, shaped by the storyteller, the reader, and the medium. Like the house’s shifting dimensions, truth in House of Leaves depends on the perceiver’s position and that position is always partial, always unstable.

Final Thoughts

House of Leaves doesn't simply tell a story, it dismantles storytelling. It invites us to examine how narratives are constructed, how perception filters reality, and how meaning is unstable. The novel isn’t solved, it’s inhabited. And in experiencing its disorientations, we confront the limits of our own interpretive faculties.

As both a text and an experience, House of Leaves blurs the border between reality and perception. It doesn’t ask what’s real, it asks what you make real. And that question lingers long after the final page.

Write a comment ...